Black Market PGR ‘Propped Up’ by the Exploitation of Vulnerable Workers

In March last year, Coles raised the price of their home-brand milk by 10 cents a carton – with an explicit promise to pass 100% of the proceeds to Australian dairy farmers. Less than a year ago, the majority of Australia was still enduring the worst drought conditions in living memory. Shoppers could hardly miss the Coles advertisements – they were everywhere, plastered all over their stores and social media platforms.

A few months later, the scheme was revealed for the scummy, exploitative corporate scam that it was. Turns out, the extra cash wasn’t being passed on – Coles was hit with a $5 million fine. Aussies were furious.

But… did they really have the right to be? It’s widely known that home-brand grocery products are worse for actual producers — the duopoly of Coles and Woolworths has gutted the Aussie dairy industry in recent years.

Consumers have some power in the market; Australians could have always voted with their feet, preferencing those who uphold responsible industry practices over those who do not. There are alternatives to home-brand milk which are available for purchase; many of these products offer more to Australian farmers, dollar for dollar. Instead, for most people, it’s about cheap milk.

This whole ‘home-brand milk’ saga displays the lack of empathy and solidarity in the marketplace. Even when it comes to small things – like milk – greed dominates our values, and the actions which stem from them.

PGR Woes Are An Extension of a ‘Broader Societal Indifference’

It’s obvious that Australian consumers have a somewhat strained relationship with primary producers, and the rapacious for-profit middle-men that exist between them. (Yes, I’m looking at you, Coles and Woolies…)

In truth, it’s because consumers in the market are alienated from the processes of production. Unless we grow something ourselves, we don’t understand what it is to grow – and in most cases, one is unlikely to buy a product if one can produce it themselves, using their own labour power.

We have ways of managing the interests of these groups when they’re ‘out of sync’, in legal industries. Utilising bureaucracy, sound industrial practices can be gradually standardised and made mandatory. Companies can receive encouragement to provide their processes with a high level of quality and rigour – and risk losing business or getting shut down, if they don’t.

Finally, audits and independent commissions can enforce laws against those who choose to flaunt them. Decriminalised (or ‘legal’) industries can effectively utilise legal frameworks; regulations and protections can be established to ensure the rights of workers, consumers and producers alike.

None of these protections exist in the context of the cannabis industry, because cannabis is still (by and large) a prohibited substance. The consumers’ generalised indifference towards the bottom line of producers, and the producers’ generalised indifference towards the health of everyday consumers, quickly morphs into an ugly ‘race to the bottom’.

This is how PGR has managed to flood Australian cities.

Not to mention, workers and employees producing cannabis in these black markets are placing themselves at great risk. Workers lack meaningful security in their day-to-day lives. The losses of criminal organisations are being taken on by the poorest in their own communities.

‘Untouchable Management’ Takes Advantage of Vulnerable Workers for Profit

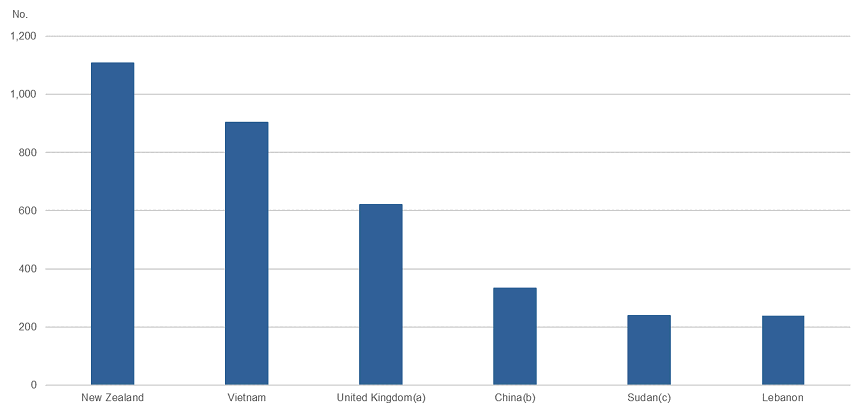

There are prison statistics, court records, and a handful of news reports available online, showing who is suffering to produce our buds… and there is one community that keeps coming up: Low-Income Immigrants. Particularly Vietnamese immigrants, whose numbers vastly exceed other groups.

Hundreds of Vietnamese people are caught by the police each and every year. They’re performing their job as ‘crop sitters‘; minding and maintaining houses filled with cannabis plants. The scale of the disparity is such that Vietnam-born residents of Australia are over-represented by 100% in our prison population.

The over-representation of Vietnamese people in prison populations isn’t the result of some evil scheme, cooked up by vulnerable immigrants. ‘Crop sitters’ are almost universally unable to get a well-paying job in the legal marketplace. They are often recruited from contexts of poverty or desperation. Trace the dark money, and it’s undeniable: ‘crop sitters’ are being used as pawns in a broader hustle.

A Game of Criminal Syndicates

You’re probably familiar with the drug bust stories posted by State Police departments on social media sites. Cops love to brag about their latest seizure of illicit substances – and cannabis grow-houses make for excellent twitter material… but, of the glut of grow-house bust-pieces floating round the Aussie news-sphere, only a handful of articles manage to successfully connect the dots between the Vietnamese ‘crop sitters’, and the criminal syndicates who pay them to operate.

‘Syndicate‘ is the word being thrown around in the press, at least. It’s a less loaded term than ‘gangs’, which tends to lump desperate ‘crop sitters’ in with violent criminals.

The ‘syndicate men‘ run the financial end of the operation. They lease houses, purchase and set up equipment, and distribute/sell the cannabis. Ultimately, however, they remain insulated from criminal risk; it’s the Vietnamese immigrants who actually grow the plants.

A Sadly Common Story

Faceless men organise a meeting with Vietnamese immigrants without any source of income, making them an offer they won’t find anywhere else:

Mind this house a few times a week, don’t ask questions, follow instructions left in the mailbox, and you’ll get paid when it’s harvested.

“You said that the person who offered you the job is named Quong, who is over 40 years of age; and Quong contacted you by leaving mail in your mail box. You met Quong twice – once at a McDonald’s, and the second time at a shopping centre. You do not know much about the identity of your boss.”

DPP v Duong and Pham [2016] VCC 1327

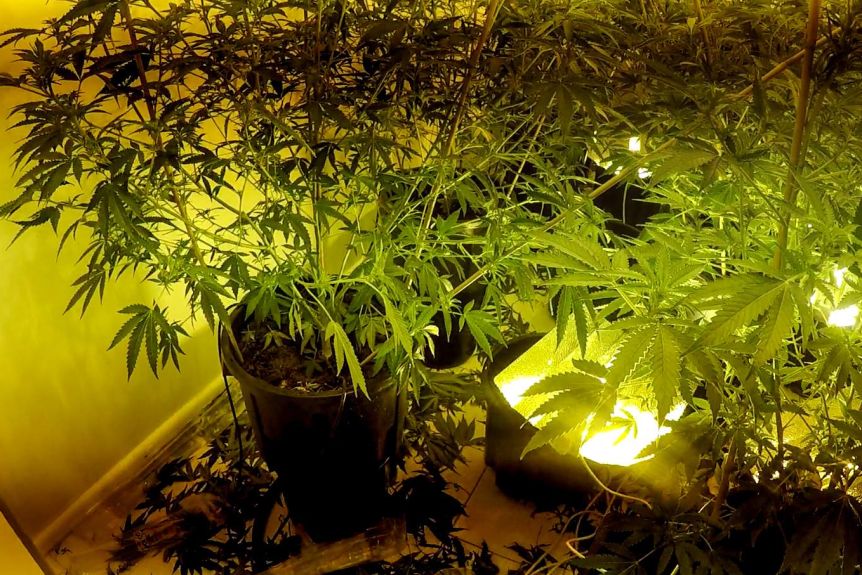

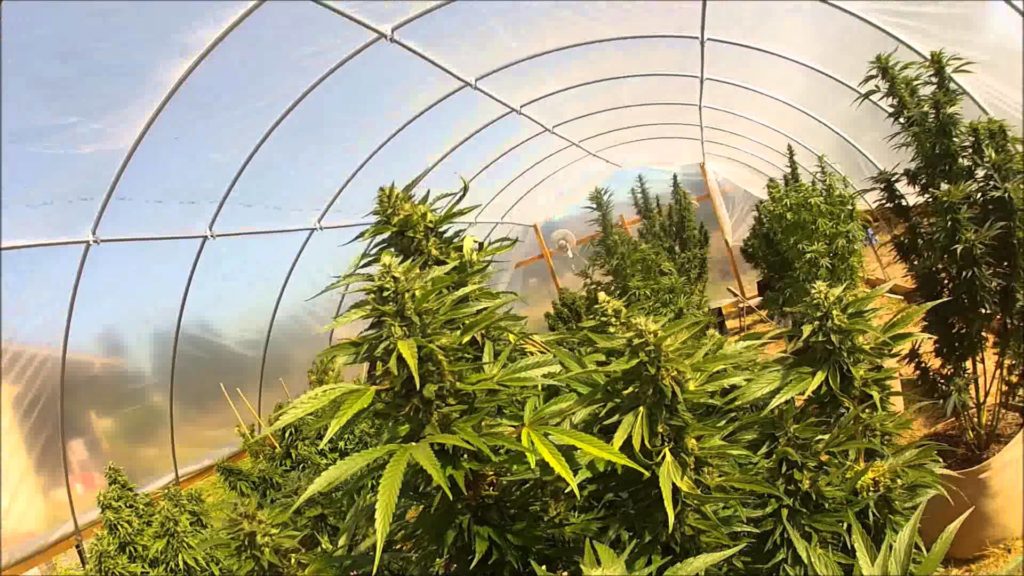

Every room in a given grow house will be filled with hydroponic equipment, lights, and as many plants as it can fit. Electricity meters are bypassed. The designated ‘crop sitter’ is expected to either visit every few days, or to live on-site for the duration of the grow. Experience isn’t necessary, but desperation often is.

There are immigrants who come into this business out of extremely low-paid farm work. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of minding a few hydroponic pipes inside of a house, in comparison to picking fruit in the sun 10 hours a day… it’s still agriculture, after all. Why not?

“You […] met a person called Mr Phoung. He offered you the sum of $500 per week to stay at the house overnight and to ‘look after the house’ in order to protect it from thieves. You claimed that you had been told not to look through the house and only to enter the living room and bedroom and bathroom.”

DPP v Vu [2019] VCC 1127

Crop-sitters are regularly arrested in every state and territory. Arrests often occur as a result of prying neighbours, tipoffs, and irregularities in power consumption. Those managing the operation remain anonymous and free from consequence.

“Over a 10 week period, [Luu’s] earnings were approximately $10,000; of which $7,000 was sent over to his parents; $2,000 were retained by him for his rental and food, and the balance was spent gambling each week. He said that prior to the offending conduct occurring, his financial means were quite desperate.”

R v Luu [2019] NSWDC 668

Ruthless recruitment strategies have been employed by black market syndicates. Some of the techniques are straight out of the mafioso playbook. Gambling is common in Vietnamese culture; addiction & debt function to create a helpless, dependent worker base. Additionally, wages are often recycled back to their employer through lost bets.

“[Dinh] had a debt of $30,000 from gambling in clubs in the Bankstown and Yagoona area. He had been approached by the principals of this cultivation, and they had told him if he worked for them for six months, he would be paid a few hundred dollars each week, and his debt would ‘go away’.”

R v DINH [2016] NSWDC 131

From Vietnam to Where?

From the outside, the domestic origin of organised crime in the Vietnamese community is still hazy. The beginnings of their international influence can be traced to the turn of the century. Australian commonwealth authorities were aware of the Vietnamese trafficking business in the 90’s; in the early 2000s, cannabis cultivation emerged as a significant business in the UK and Canada for Vietnamese syndicates.

News reports suggest that organisations based in Canada spread the practice of the ‘hydro grow house’, and bypassing the meter. It emerged as a model adopted by immigrant communities in a handful of countries.

‘Crop sitters’ are often caught with hundreds of plants, and many kilos of dried cannabis. Prosecutors are acutely aware of the limited role of ‘crop sitters’ in the broader activity of the ‘business’ – as well as their rank exploitation by violent criminals.

Consequently, sentences for ‘crop sitters’ tend to land in the lower range – between 1 to 3 years – with a near-ubiquitous reference to criminal punishment for “general deterrence“ (not that it ever seems to work).

“It must be a term of imprisonment which gives rise to the application of general deterrence”

DPP v Nguyen [2019] VCC 1858 — sentenced to 2 years, 9 months.

“…It has got to be a circumstance where general deterrence is the principal part of this sentencing process.”

DPP v Nguyen [2019] VCC 1732 — sentenced to 18 months.

“…for the purpose of general deterrence.”

DPP v VO [2019] VCC 1734 — sentenced to 16 months.

‘Crop Sitters’ Aren’t the Real Criminals

There is a broad recognition within the court system that ‘crop sitters’ are not criminal masterminds in disguise. Still, the fact remains; ‘crop sitters’ are the ones getting regularly prosecuted in place of their bosses, the ‘syndicate men’ – the true masterminds.

Police are struggling to track down those in charge of these giant operations. In April last year, The West Australian reported the arrest of 43-year-old Xuan Dao, a man supposedly “at the very top of the tree [in Australia]”. He allegedly received 6 ½ years for his role in supplying and managing grow houses in Perth. I was unable to find court records supporting this claim – records only go so deep.

Syndicate ‘Grow Houses’ Likely Produce the Majority of Australia’s PGR Buds

Let’s take our focus back to Australian cannabis consumers. The black market in Australia has been caught in the midst of a PGR epidemic. Turns out, you can attribute a lot of the dirty, clumpy, poor-quality PGR weed to criminal syndicates, who often require ‘crop sitters’ to use Plant Growth Regulators in their operation, as a means to increase yield size (and profits) – without regard for the health implications for the consumer.

Poor growing conditions and shoddy management of these grow houses contributes to the horrible quality of these buds. Grow houses are infamous for producing shit weed – Bikie Bud’ and ‘Asian reds’ are nicknames for PGR-treated cannabis, across parts of Australia.

It’s important to emphasise that prohibition empowers the aforementioned dynamics, placing them on steroids. In locking down the industry, the field is opened up to money-hungry gangs. These parties would simply not be involved under a legal framework where cannabis is decriminalised.

We haven’t gathered enough data to make a direct correlation between the activities of these criminal syndicates, and the surge of PGR Buds across Australia. This amounts to more of an informed suggestion. Crucially, there is not enough publicly available information concerning the scale of these syndicates, their networks of distribution and sale, and the relationships they have to other circles in organised crime.