Smoking Hash With Afghani Militants

Australian comedian and radio personality Jonathan Atherton retells his escapades travelling through The Middle East in the 1980s – including his experience getting totally munted with some of the world’s most fearsome warriors — the Afghani Mujahideen. Speaking with us over the phone, he retold the insane story in stark detail. Get ready for a near-death hot-box hash trip of psychedelic proportions – and if that somehow doesn’t do it for you, just wait until you hear about the guerrilla commanders bribing heavily armed Russian soldiers with hash stashes. This is how Jonathan kept himself alive with a bit of staunch anti-Americanism. This is the whole damn story — in all its glory.

Jonathan Atherton

“Back in the 80’s, I was bumming around the third world – bouncing between China and The Congo. Buying things here and selling them there, to keep the money rolling in. In 1985, I found myself in Afghanistan.

I was interested in buying some tribal jewellery, rugs and the like. In Peshawar, I bought a number of items at the ‘Saddar Bazaar‘ from an Afghan guy called Khoja. He was a really cool dude; we drank coffee, […] smoked hash, […] and talked about world politics.”

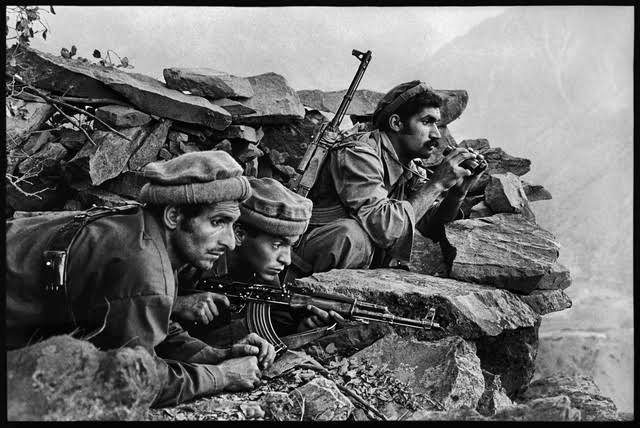

Brave Freedom Fighters

“It turned out he was a member of the Mujahideen*; ‘back in the days’ when they were the ‘good guys’, fighting the Russians.”

[Khoja] was in Pakistan to raise money, so he could buy arms […] because while the Americans were donating guns and bombs and rocket launchers to the Pakistani government, which were supposed to be filtering down to the Mujahideen […] the Pakistani government had [instead] filtered them to Kashmir, where they were fighting a war against India.

*Mujahideen (Arabic: مجاهدين mujāhidīn) is the plural form of mujahid (Arabic: مجاهد), the Arabic term for one engaged in jihad (literally, “struggle”).

“In those days, the Mujahideen acquired most of their weapons from Russians; [mostly] young Russian soldiers. Much like the Americans in Vietnam — the Russians had become drug addicts. In this case, it was opium. The Afghans were kind to the opium addicts; they looked after them — and in turn, bought weapons [that had been] pilfered from the Russian arsenal.

[…] I was only twenty-something at the time – [so] I was, of course, indestructible – ready for any adventure. Khoja asked me to accompany him and some of his men to an area outside Jalālābād, where they would regroup after the winter.”

“See, the Afghans are so entrenched in warfare […] they actually have fighting seasons, much like we have cricket seasons and football seasons.”

“In the freezing Afghanistan winter, it is just too cold for any machinery to work — helicopters don’t take off, guns don’t fire. [Instead] they spend this time to raise funds, helping to arm and resource their men.”

” […] I thought – well, a bit of a trek into Afghanistan sounds like fun — why not?”

“We set off some days later to the outskirts of Jalālābād, [arriving at] a Mujahideen safe house [that] was waiting for troops from all over to regroup and recommence the season of battle.”

“There were about 12 of us making the trek […] and it was the most arduous trekking I’ve ever done, in my life!

We traversed such narrow cliffs and paths, that even mountain goats had a hard time keeping their footing [up there].”

“We took a secret way just north of the Kyhber pass, as [the pass] was well patrolled.”

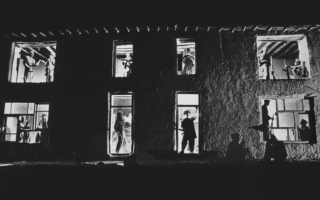

The Safe House

“After many days, we eventually reached the safe house. Upstairs was a large room, and beneath it, a basement. Over the coming days, Afghan fighters from various regions arrived to form their squads. I could hear the sounds of women from the basement, laughing and cooking — though, I didn’t actually see any during my stay. One of the men would go up, to bring down food and coffee, […] we ate bread and a curry-kind of dish. Meagre supplies, but enough to sustain us.

All through our trip, the Afghan soldiers were leering at me […] for they may not be gay in the Western sense of the word, but they do have a saying: ‘women are for children; boys are for pleasure.'”

“I managed to hold them off by saying I was Khoja’s special friend. As he was their commanding officer, they respected that — and left me alone.”

“Late on the night that we arrived in the safehouse, Khoja asked me if I’d like to join him in his “special room“. The other men were nodding and encouraging me to join him. I knew at this moment, I had no choice but to acquiesce to Khoja’s demands.”

“I was in a foreign country; had no idea where I was, and I was surrounded by some of the fiercest warriors this planet had ever produced. […] All of them were heavily armed with kalashinkovs.”

“I figured, “Maybe I’d be able to talk him out of it — maybe he just wanted the kudos of having slept with a white man?!? Or, perhaps I could perform the lesser of two evils — and just give him a blow job? What the hell, there are worse things in life…”

So I went with him to his “special room“. He opened the door: a heavy teak wooden door, leading to a room no bigger than a hotel bathroom. The walls were decorated with knives, scimitars, whips, leather bridles, saddle bags… and I thought: ‘Fuck. This guy is into the kink.'”

“In the middle of the room, a small clay pot – in which coal was burning… I thought, ‘Well… I guess we’re going to have to do it standing up.’

Khoja sat himself on the far side of the little clay pot, crossed his legs, and motioned for me to sit on the other side and close the door behind me.”

” […] There I was, in this tiny cupboard-like space, with no windows and no ventilation, surrounded by what I later find out to be the tribal accessories of his ancestors — famous horse warriors.

We talked about politics, we talked about war, we talked about the ulterior motives of the U.S. and Russian governments, we talked about sex, we talked about cigarettes, we talked about children, we talked about the Quran — we talked everything under the sun. And as we talked, Khoja reached into a leather saddle bag.”

“From the saddle bag he produced a slab of the finest Afghan hash I have ever seen in my life. When I say “slab” I mean it must’ve weighed two or three-hundred grams. The smell almost knocked me out — and it wasn’t even burning.”

A Shared Ritual of Respect

“Over the fire, he placed a grate — about six inches above the smouldering coals — and on the grate, he placed the hash. […] we continued our talk about life, the universe and everything.

I started to feel quite relaxed. I realised this wasn’t a sexual encounter; it was personal interchange — an exchange of ideas, a bridge between two cultures. It felt like a really beautiful moment.”

” […] as we talked, the slab of hash began to smoulder itself; the corners were glowing red, and smoke was rising off of it.”

“It started smouldering more and more; it never actually caught on fire […] but as it smouldered, the smoke billowed, reaching the [ceiling], and slowly descending down on to the floor – like the final curtain of a Greek tragedy.”

“Every breath I took was a lungful of pure Afghan Black. Every lungful got me higher and higher.

The smoke was getting thicker; the only light in that windowless room came from the embers of the coal fire. It was dark, and the smoke only made it darker. The air was so thick, you could cut it with one of the knives hanging on the wall.

I started to hyperventilate. I could feel the beginning of anxiety. A panic attack was coming on, as I was becoming more and more stoned. […] the smoke was so thick, I couldn’t even see Khoja anymore. I didn’t know which way was up, down, left, or right — I didn’t even know where the fuck I was. I just knew I was drowning in the thickest quicksand of hashish smoke that anyone could imagine.

I panicked.

I flailed around in that room, knocking things off the wall. A sword fell to the ground, almost skewering my foot. Leather straps from the horses of his ancestors fell on top of me, I felt claustrophobic, tied down […] like I was in bondage – and I screamed.”

“[…] as I screamed, I couldn’t even remember where the door was, or where I was. I felt that I was deep in a cavern, beneath the surface of the earth.”

“The troops in the room next door could hear my panic, and the door behind me was suddenly opened […] two strong Afghan Mujahideen grabbed me and pulled me out of the room. I laid there, in the common room, for what seemed like an eternity. Staring at the ceiling […] seeing the entire universe above me.

I wasn’t just stoned: I was tripping. It was a transcendental state. I felt both at-one with the universe, and […] alienated from it.

As I came down, they offered me strong Afghan coffee, and a kind of sweet cake to eat. After an hour or two, I had levelled out; and spent the rest of the night in a blissful state of hash-induced euphoria.”

“Throughout the night, men would go into that small room, close the door behind them, and reappear a minute or two later — as high as the price of airport coffee. But Khoja remained in the room alone, sitting cross legged on the other side of the coal burner, inhaling the smokey fruit of a two-hundred gram slab of Afghan black.

He remained there for about 12 hours until the coal fire had gone out and the hash had been fully consumed.

In the morning, one of the men opened the door. The stench was so strong, it would put to shame any Amsterdam coffee shop.

Khoja remained seated in the same position, cross-legged, cross-armed, eyes closed; like a statue. He was both stoned and stone. Two men lifted him from under his arms, carrying him out to the common room. His legs, still crossed in a seated position, [hung down as] they placed him down onto the floor, atop a hand-woven Afghan kilim (traditional rug).

Someone tilted his head back and pinched his nose, causing him to open his mouth. They then poured luke-warm Afghan coffee down his throat. He gagged and spat, unfolding his arms and legs, and staggering to the window. He leaned out into the icy air, and vomited profusely.”

“He straightened up — staunch and strong, eyes glowing with rage, his face set in grim determination. He wiped the remnants of spew from his chin. [Looking] me square in the eyes, he said: ‘Now. Now I kill Soviet.'”

“If I don’t kill all the Soviet, my son will kill Soviet. If he fails to kill all the Soviet, his son will kill Soviet — until there is no more Soviet in Afghanistan.”

“At this point, I actually felt sorry for the Russians; how could anyone defeat this kind of determination? There is no way a political campaign could ever defeat a people so united by passion, […] so hardened by centuries of war. The Afghans have never been defeated; this is a lesson the Americans are learning at the moment.

After a couple of days, there were about sixty men in the safe house. Two of them said they would escort me back to somewhere near the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

They left me twelve kilometres inside of Afghanistan, and pointed me towards the border. They wished me well on my journey; we embraced, there were tears, and I wished them all the success in their campaign.”

“As I walked down that road towards Pakistan, a Jeep came rolling up behind me. It was a Russian Jeep. There were four soldiers in it; they pulled their guns, and pointed them at me.”

Negotiating With Soviet Soldiers

“Khoja had gifts for me — a kilo of Afghan hash, as well as a number of rings and bracelets, of silver, Turkmen and carnelian — all loaded into a handwoven saddle bag, made by his grandmother.”

“The Russians discovered the hashish and the jewellery. They started interrogating me in their language. I couldn’t understand a word; well — just one. The word ‘American’… to which I responded by spitting on the dirt and repeating the word ‘America’ in disdain. I spat again, in the dusty soil, and repeated with even more disgust: ‘America?!'”

“‘I’m Australian!’ I said – while mimicking the jumping of a kangaroo.

At this point, they laughed.

One of them started to speak to me in French, because it was evident that none of them could speak English. I responded in German, saying: ‘I can’t speak French, but I can German?’ to which one of the soldiers replied in ‘I can speak very good German also’. It turned out he’d trained with the East German Stasi (Staatssicherheitsdienst, SSD), and was fluent.”

“He asked ‘what are you doing here in Afghanistan?’ and I replied ‘Afghanistan? No; this Pakistan, isn’t it?’

He said ‘No, Pakistan is 10km there’, pointing to the border.

I told them that I’d been walking… and we must be in Pakistan, otherwise I was lost…

Well, they confiscated the hash from me, leaving me with the jewellery and saddle bag, drove me to within 2kms of the border. We smoked together, got high, had some laughs, and I found my way back to Peshawar, safe and sound… as well as secure in the knowledge that the Afghan people will never be defeated.”

Ahole, what makes you think boinking your flat white ass is some sort of prize to anyone? You people are so mentally sick with narcissism it would be comedy if it weren’t tragedy.