Table of Contents

The ‘Australian Cannabis Summit‘ was an online conference held in Brisbane this year between the 5th and the 6th of July. A wide diversity of speakers from various walks of life were present. Luckily, the live videos still remain online for all to enjoy, so don’t worry if you missed out! A lot of these videos are top notch; we recommend you check them out for yourself, if you get some spare time.

We at Friendly Aussie Buds loved the ACS so much that we’ve taken the liberty of searching through these videos for the juiciest, most interesting information available. In this article, we’ll be focusing on John Jiggens’ presentation, where he spares no effort in covering the rich history of cannabis and hemp production in Australia throughout the years. Knowing the history of the hemp plant in our country is a necessary key for unlocking the pathway to full cannabis legalisation.

Hemp Colony

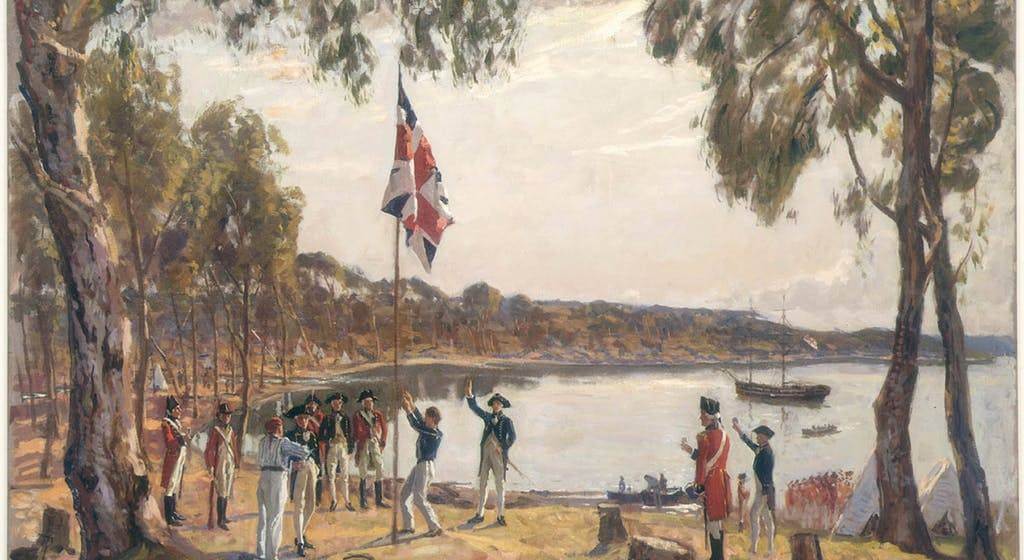

Jiggens, a historian in his own right, explores the strong possibility that Australia was invaded and colonised by the British for the express purpose of growing hemp plants. Historical documents and accounts have shown that large tracts of New South Wales were envisioned by the British not simply for the purposes of housing prisoners. Rather, this land was to be developed into a ‘productive’, hemp-producing powerhouse.

This can be a surprise to modern Australians; who, over the space of several generations, have become accustomed with the criminalisation and tight controls associated with cannabis. For the settlers, however, the contemporary connotations attached to the recreational use of Cannabis Sativa were simply not there.

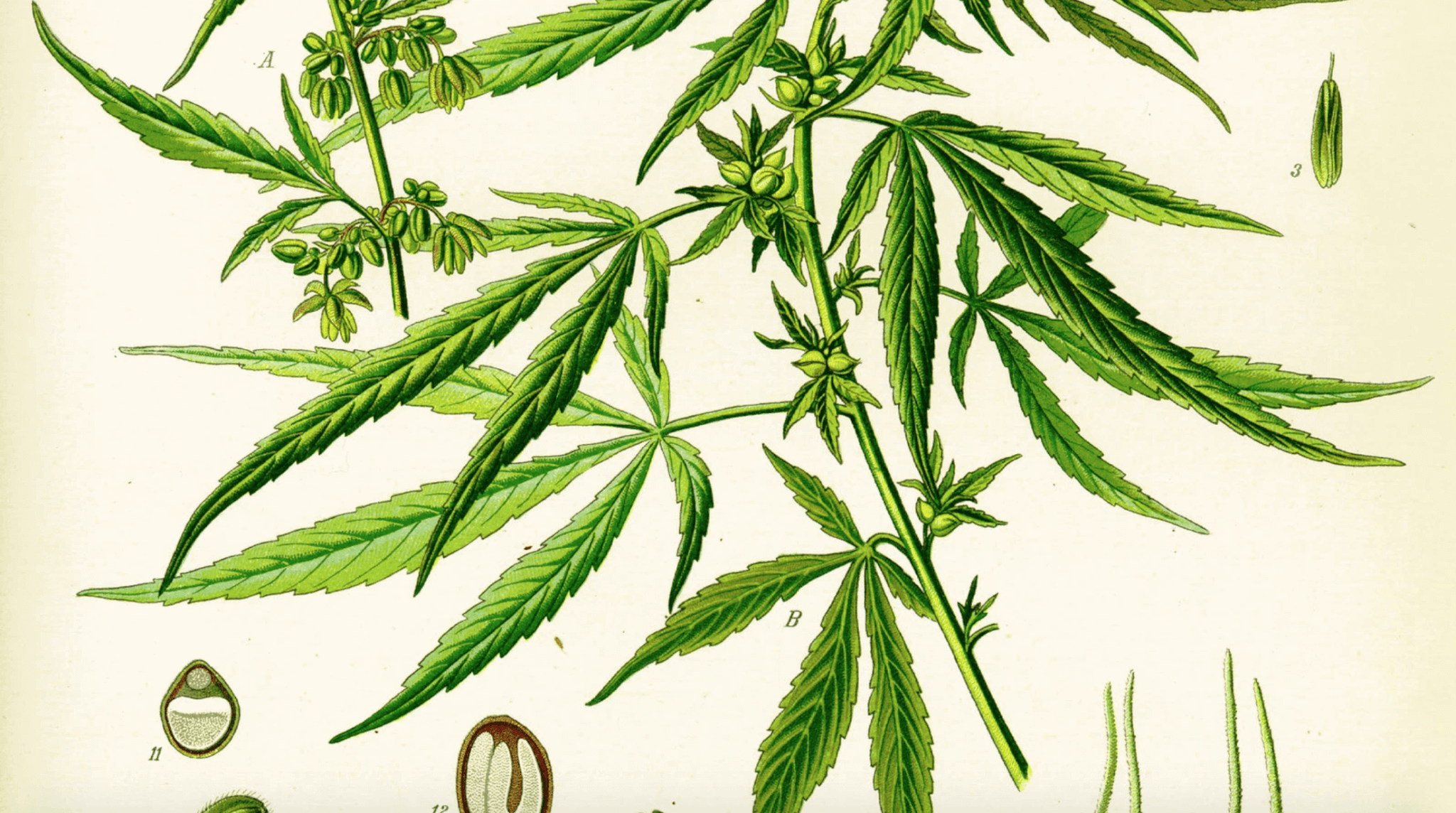

In the golden age of sailing, it was the fibres of the hemp plant itself that were the prized commodity. Back in the day, the material was commonly utilised for many different purposes. The word ‘canvas’ was initially Dutch for ‘cannabis’. Hemp provided the technological basis for trade, war and colonial ventures. It was crucial to kitting out the earlier warships of the time. To fit out a first class ship of war required 80 tons of hemp. This equated to 320 acres, or half a square mile, to cultivate all those crops. Producing hemp in these times was not only common; it was a necessary, and highly profitable venture.

Before hemp was slandered as ‘marijuana’, it was perhaps one of the most important plants on the face of the Earth. Since then, a global campaign against cannabis has been waged, which has managed to fuel an irrational stigma and societal panic with varying degrees of success.

The Founders Were Cooked

Sir Joseph Banks was one of the founders of settler Australia. Little known fact: in a similar fashion to many of the founding fathers of the United States, Banks was, in fact, a cannabis enthusiast. He was the one who ordered hemp to be shipped over with the First Fleet, on account of ‘commerce’…

Of course, the justification for British ‘settlement’ that we all heard in school had something to do with the necessity for an alternative outlet to the growing surplus convict population. Yet it could be easily argued that the cost for this undertaking were so great that colonisation would not have been worth it. There are considerations, such as competition from other colonial European states, which may have come into play if the British had not claimed Australia as a colony. But this explanation on its own is probably too simplistic and naive. If this is so, it indicates that there could be other, more hidden reasons for the establishment of Australia as a prison colony.

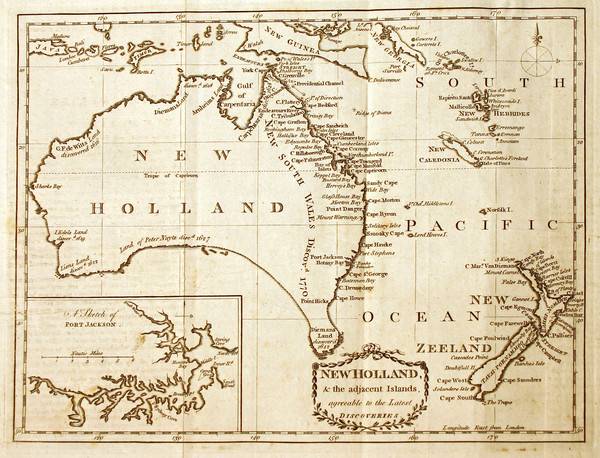

Yes, that’s right: the colony of New South Wales was likely created to establish an alternative supply for hemp. We can surmise this by looking back into some of the surviving documentation from the era. During the Georgian period (1776 – 1815), Britain recurrently expressed its need for a hemp colony in its strategic planning.

Cannabis Sativa seeds first arrived in Australia in 1788 on the First Fleet at the request of Banks. The blueprint for the New South Wales colony, approved by the British Cabinet in 1786, envisaged Australia as a commercial colony producing hemp. In 1892, the Department of Agriculture distributed Cannabis sativa seeds to hundreds of farmers in New South Wales, as an ‘experiment’ in the cultivation of hemp. This was due to the high prices of binding-twine at the time. In 1797, old mate Banks joined the British Board of Trade, assuming control of all of the United Kingdom’s hemp supply.

In 1802, Banks filed a report to the Board of Trade. In it, he refers extensively over several hundred pages to the ‘Indian hemp experiment’. India was a similarly British colony where the production of hemp had already been trialled. It may come as a shock today, but the existence of a recreational ganja was a complete curiosity to Banks. Cannabis Indica was far more genetically distinct from Cannabis Sativa at this time. Indian hemp was potent to the point of inebriation, and also had medicinal uses; unlike British hemp, which was used almost exclusively for its fibre. The British discovered this themselves when they attempted to establish Cannabis Indica plantations for fibre production, only to eventually realise that the Indian counterpart did not possess the same fibrous qualities as their treasured Sativa. They literally tried to turn dope into rope – and failed spectacularly.

These bioregional differences are what eventually spawned the (controversial) ‘polytypic theory’ of cannabis species. According to this theory, cannabis can be classified under either Sativa, Indica or Ruderalis, depending upon the properties of its genetic expression. When prohibition began, Cannabis Sativa was criminalised in the exact same way to Cannabis Indica, leading to the eventual demise of the hemp industry. In recent years, the crossbreeding of these ‘species’ has placed increased ambiguity between genetic varieties; and increasingly, hemp is making a revival. The search for sustainable alternatives to commonly used materials has led hemp to become the king of revegetating economic life.

The Great Southern Land

Banks’ report on the Indian hemp experiment had direct implications for the Australian hemp experiment. The Indian hemp trial did have similarities to the New South Wales trial, although there were key differences. The failure on behalf of the British to develop a productive Sativa hemp colony in India is part of what led them to aggressively explore other possibilities in the region. At any rate, the fledgling colony of Australia once played a central role in the expansion of British hemp supply. One of the 15 paragraphs within the first document of Australia refers to hemp as a ‘strategic asset’. This makes sense historically, considering the fact that just a few years prior, Britain was dealt a serious blow in the United States’ War of Independence, where they lost control of territories that produced key resources and assets for the Empire.

Admittedly, there is a severe lack of substantive documentation around this fact. We exist in the wake of a historical vacuum. There is still much about our past which has yet to be uncovered. Yet, we do know that from 1840, up until the early 1900s, Australians used cannabis as a legal, medicinal herb. ‘Cigares de Joy’ (cannabis cigarettes) were sold over the counter throughout the land. ‘Yandi‘ became a delicacy among the remaining indigenous families.

The Hunter Valley Incident

Up until The Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was adopted in 1961, Australians enjoyed a sense of relative liberty when it came to their relationship with Cannabis Sativa. Then, all of a sudden, everything changed. In 1963, attention was drawn towards large deposits of Cannabis Sativa growing alongside the rivers and creeks in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales. Bohemians would risk being caught by the Police and landowners to harvest the tops of these wild-growing heads.

The popularity of cannabis exploded overnight. Soon, dairy farmers were demanding that something be done to protect their land from trespassers. Police did all they could to eradicate the plant, but it took over 9 years for the infestation to end.

This officially signalled the end of legal cannabis in Australia. Yet, this event also spawned the beginning of a counter-cultural movement that would eventually evolve into the Nimbin Aquarius Festival in 1972. That movement looks very different now, but is still going strong today, as the influence of cannabis has come to spread all across the nation.

As for what’s next in the history of Australian cannabis? Well, we’re writing this chapter; so, it’s up to us! It may even become possible for Australians to reclaim our legacy with hemp, as we move forward in ever more creative and expressive ways.

Works Cited

[1] Australian Cannabis Summit – The History of Cannabis in Australia

[2] https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/wj8e8m/was-australia-colonised-to-grow-cannabis

[5] https://hemp.org.au/cannabis/colonial-history/

[6] https://friendlyaussiebuds.com/education/history-cannabis-australia/

hi this is nice?

hi my name is nigythn nice to meet you, was it mitch

?